In this guide

The amount of money you should have in super to make it worthwhile setting up your own self-managed super fund (SMSF) is a contentious issue.

Over the years there has been much discussion of the issue by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), which administers SMSFs, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), which regulates the financial industry, and the Productivity Commission. The consensus was that having at least $500,000 in super is a good yardstick, but this was challenged by the SMSF sector which eventually commissioned its own research.

The latest research by the University of Adelaide for the SMSF Association found SMSFs with $200,000 or more in net assts can be competitive with industry and retail funds both in terms of cost and investment performance. The February 2022 report – Understanding self-managed super fund performance – was based on analysis of over 318,000 SMSFs for the three years to June 2019.

These findings complemented earlier research by Rice Warner, also for the SMSF Association. The Cost of operating SMSFs 2020 report also found SMSFs with at least $200,000 in assets were cost competitive on average. But it went further, comparing SMSFs of different sizes and complexity with retail and super funds on a like-for-like basis, with some surprising results.

In this article, we’ll provide you with the latest statistics and perspectives on this vexed issue to help you make your own informed decision.

Allow for set-up costs

One of the issues that skewed previous attempts to quantify costs was that there was no breakdown of one-off set-up costs and ongoing expenses associated with operating your own SMSF. This meant set-up costs incurred in the first year of operation only, skewed the average for all funds.

Free eBook

SMSF investing essentials

Learn the essential facts about the SMSF investment rules, how to create an investment strategy (including templates) and how to give your strategy a healthcheck.

"*" indicates required fields

There is also a wide range of ongoing investment fees and other costs that reflect the range and complexity of SMSFs themselves, so averaging costs across the sector can be misleading. That said, it’s obviously important that the benefits outweigh these costs, if not in the first year, then within a reasonable timeframe. Otherwise, you may be better off in a public fund with lower costs on your time as well as your finances.

Set-up costs include professional legal and accounting advice to establish the SMSF’s trust structure and trust deed.

Ongoing costs for services and reports required by regulation include:

- The preparation of financial statements

- The preparation and submission of a tax return to the ATO

- The payment of a compulsory annual SMSF supervisory levy to the ATO

- A corporate trustee fee (if applicable)

- An annual audit of all financial records. This must be conducted by an ASIC-approved auditor to ensure that all fund activities are fully compliant with super legislation.

An SMSF may also need to pay actuarial costs to determine eligible member pension payments.

While these ongoing costs can’t be avoided, trustees can reduce their costs by handling some of the fund’s administration themselves.

Then there are optional costs, such as fees for professional investment advice or management services (if fund trustees choose to hire them).

And it doesn’t end there. There are also costs associated with winding up an SMSF. The amount will depend on the complexity of your SMSF’s financial arrangements and the wind-up process.

While recent research indicates $200,000 is a reasonable starting balance for an SMSF, there are caveats.

Manage your SMSF smarter – for free

Access practical, independent guides and checklists to help you run your fund with confidence with a free SuperGuide account.

Find out moreWhen $200,000 is not enough

One of the main reasons people give for running their own SMSF is the control it offers. But if control delivers poor returns relative to large funds, the benefits may be illusory.

The University of Adelaide report found SMSFs generated greater variation in returns relative to large funds. They had a higher propensity both to overperform and underperform, perhaps reflecting a wide variation in financial acumen but also in the broad range of investments available.

The report found SMSFs with more than 80% of their assets in cash and term deposits were not cost competitive, even when they had more than $200,000. Each increase in asset classes (up to four) was associated with an improvement in returns, while further increases up to seven asset classes also improved returns but at reduced rates.

Yet there are circumstances when it may be appropriate to set up an SMSF with less than $200,000.

SMSFs with less than $200,000 are generally only appropriate if you expect your fund to grow to a competitive size within a few years. Indeed, the majority of SMSFs with low balances either grow relatively quickly or are late in the drawdown phase and preparing to close.

The latest ATO statistics show the only age group with a median balance of less than $50,000 is under 34-year-olds. The median balance rises to $110,000 for members aged 35–44 but doesn’t pass the $200,000 mark until members are in their early 50s when the median balance is $223,000.

How do SMSF costs compare?

While there is a growing consensus that it can be worthwhile setting up an SMSF once you have $200,000 or more in super, the cost-benefit analysis will also depend in part on your willingness, or not, to carry out some of the administration tasks.

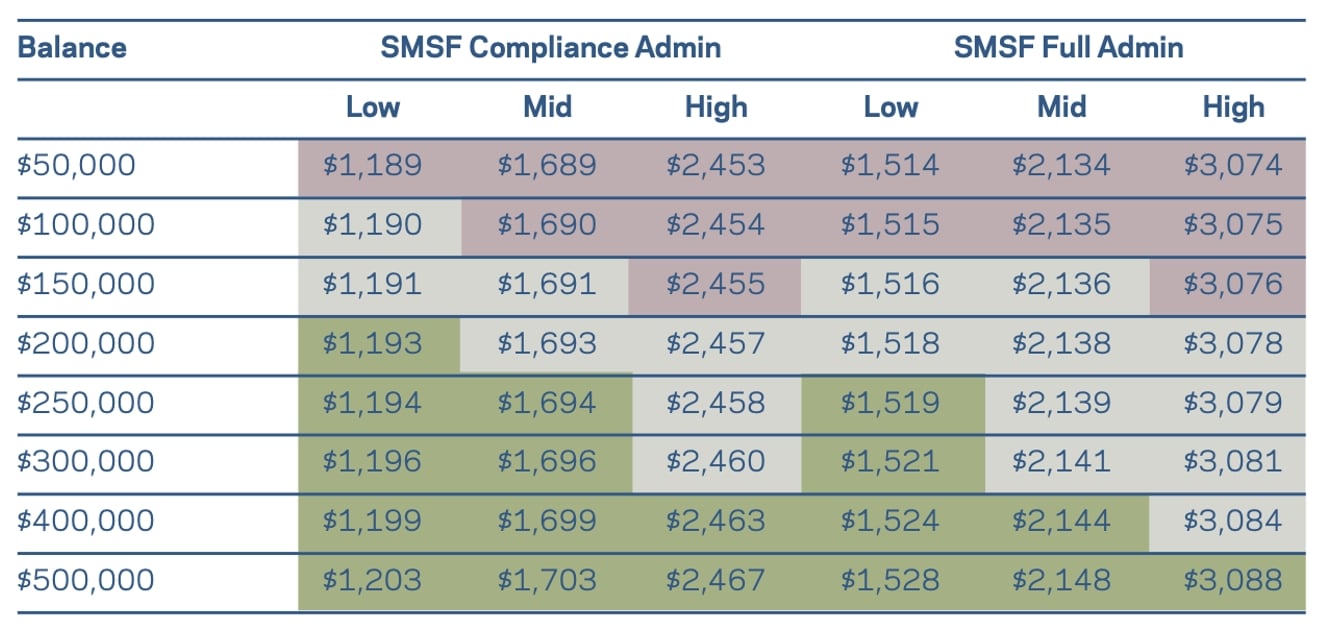

Rice Warner examined the costs for the set-up and running of SMSFs with different balances, whether trustees outsource only their compliance administration or all their administration, and whether funds use low, medium or high fee services.

Supercharge your SMSF

"*" indicates required fields

The table below shows the range of costs for SMSFs of various size balances with shaded areas indicating whether the fees are above, within or below the range for retail and industry super funds with similar balances.

Comparison of annual costs of SMSFs (accumulation accounts)

SMSF fee above range for retail and industry funds

SMSF fee within range for retail and industry funds

SMSF fee below range for retail and industry funds

Source: Rice Warner: Cost of Operating SMSFs 2020

As you can see from the table, SMSFs with balances of $500,000 or more are generally cheaper than retail or industry funds.

What’s more, funds with balances of $200,000 or more provide equal value to retail or industry funds at all levels of administration.

Rice Warner also found that comparisons for SMSFs in accumulation and retirement phase were similar, as were those with a single member or two members.

As expected, SMSFs with balances below $100,000 were generally more expensive than retail or industry funds. According to the latest ATO statistics, 20% of SMSFs established in 2019–20 held less than $100,000 in assets (but only 7.6% of SMSFs overall), while 40% held less than $200,000 (14.2% of funds overall). Once again, this shows the majority of funds grow to size where they become cost effective.

The high cost of direct property

As mentioned earlier, the number and type of assets also has a bearing on SMSF performance. While this is the case regardless of fund size, the issue is more acute for SMSFs with a relatively low balance concentrated in a small number of assets or assets classes.

SMSFs have been criticised in the past for a lack of diversification, and the latest ATO statistics show that this is still an issue. In June 2020, a staggering 41% of SMSFs held 80% or more of their assets in one asset class and 8% held all their assets in one asset class. Of this latter group, 40% had assets of less than $50,000, but 16% had assets of more than $500,000. Part of the problem is the popularity of investments in real property, both residential and commercial.

Manage your SMSF smarter – for free

Access practical, independent guides and checklists to help you run your fund with confidence with a free SuperGuide account.

Find out moreOne of the benefits and attractions of SMSFs is that they are the only type of super fund that allows members to invest in direct property. But this comes at a significant cost.

Rice Warner also did an analysis of total fees incurred by SMSFs with and without direct property investments. While median fees for SMSFs without direct property are competitive for balances of $200,000 or more, median and high fees for those with direct property are higher than the highest fees for retail and industry funds of all balance sizes.

Taking the example of SMSFs with a balance of $500,000 in 2019, median fees for funds without direct property were $3,207 compared with $9,969 for funds with direct property. Funds with the same balance but high fees had total fees of $15,908 without direct property and $29,799 with direct property.

This pattern of total fees was repeated for funds of all balances. The report attributed this to the higher investment costs of servicing direct property compared with other investments, and higher administration costs for accounting and related services.

This highlights the importance of doing your own cost-benefit analysis when considering an SMSF. For some SMSFs, investing in direct property may not stack up financially against other types of investments. For others, especially those with business property, the benefits of holding property in super may be worth the cost, especially when compared with the cost of holding property outside super.

The bottom line

There is a growing consensus that you need $200,000 or more in super for an SMSF to be cost effective, although less may be appropriate if you expect your balance to grow quickly.

SMSF costs are proportionally higher for funds with lower balances and less competitive with other types of super funds. These costs include establishment, ongoing and wind-up expenses, but also non-financial costs such as time you spend operating your fund. So, if you are considering setting up an SMSF, it’s important for the benefits to outweigh the costs or you may be better off with an industry or retail fund.

The information contained in this article is general in nature. It’s best to seek independent professional advice to determine whether setting up an SMSF is appropriate for your individual financial needs and circumstances.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.